Electronic mail: clients

mutt

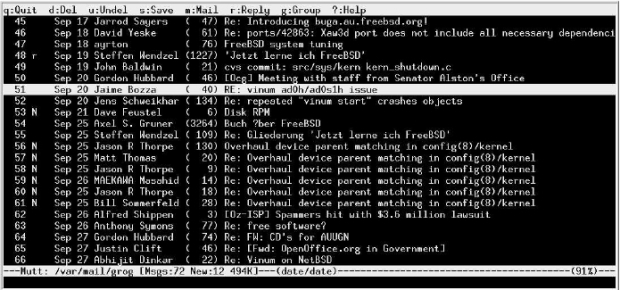

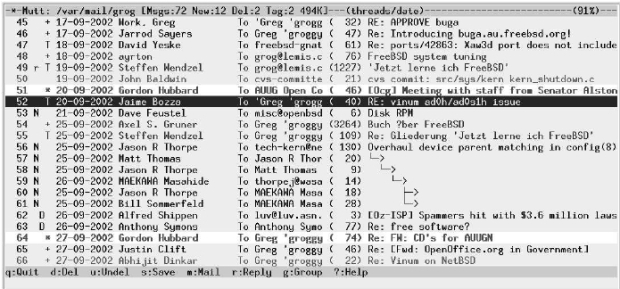

In this section, we'll take a detailed look at mutt. Start it by typing in its name. Like most UNIX MUAs, mutt runs on a character-oriented terminal, including of course an xterm. We'll take a look into my mailbox. By default, when starting it up you get a display like the one shown in Figure 26-1 .

mutt sets reverse video by default. You can change the way it displays things, however. On page 481 we'll see how to change it to the style shown in one shown in Figure 26-2 .

The display of Figure 26-2 shows a number of things:

- The line at the top specifies the name of the file ("folder") that contains the mail messages (/var/mail/grog), the number of messages in the folder, and its size. It also states the manner in which the messages are sorted: first by threads, then by date. We'll look at threads further down.

- The bottom line gives a brief summary of the most common commands. Each command is a single character. You don't need to press Enter.

- The rest of the screen contains indexlines, information about the messages in the folder. The first column gives the message a number, then come some flags:

- In the first column, we can see r next to some messages. This indicates that I have already replied to these messages.

- In the same column, N signalizes a new message (an unread message that has arrived after the last invocation of mutt finished).

- The symbol D means that the message has been marked for deletion. It won't be deleted until you leave mutt or update the display with the $ command, and until then you can undelete it with the u command

- The symbol + means that the message is addressed to me, and only to me. We'll see below how mutt decides who I am.

- The symbol T means that the message is addressed to me and other people.

- The symbol C means that the message is addressed to other people, and that I have been copied.

- The symbol F means that the message is from me.

- The symbol * means that the message is tagged: certain operations work on all tagged messages. We'll look at that on page 481.

- The next column is the date (in international notation in this example, but it can be changed).

- The next column is the name of the sender, or, if I'm the sender, the name of the recipient.

- The next column is the name of the recipient. This is often me, of course, but frequently enough it's the name of a mailing list. You'll notice that this is a column I have added; it's not in the default display.

- The next column gives the size of the message. The format is variable: you can specify number of lines (as in the example), or the size in kilobytes.

- The last column is usually the subject. For messages 56 to 61, it's a series of line drawings. This is threading, and it shows a relationship between a collection of messages on the same topic. Message 56 was the original message in the thread, message 57 is a reply to message 56, and so on. Messages 60 and 61 are both replies to message 59. mutt automatically collects all messages in a thread in one place.

You'll notice in the example that the lines are of different intensity. In the original, these are different colors, and they're a matter of personal choice; they highlight specific kinds of message. I use different colors to highlight messages on different topics. If you're interested in the exact colors, see http://ezine.daemonnews.org/200210/ports.html, which contains an early version of this text.

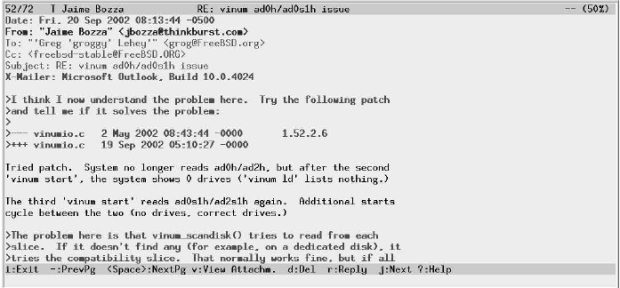

The index line for message 52 appears to be in reverse video. In fact, it's in white on a blue background, a color I don't use for anything else. This is the cursor, which you can position either with the cursor up and cursor down keys, or with the vi-like commands j (move down) or k (move up). In the default display, it is in normal video (i.e. not reversed, or doubly reversed). You can also move between pages with the left and right cursor commands. Many commands, such as r (reply) or Enter (read), operate on the message on which the cursor is currently positioned. For example, if you press Enter at this point, you'll see a display like that in Figure 26-3 .

Here, the display has changed to show the contents of the message. The top line now tells you the sender of the message, the subject, and how much of the message is displayed, in this case 50%. As before, the bottom line tells you the most common commands you might need in this context: they're not all the same as in the menu display.

The message itself is divided into three parts: the first 6 lines are a selection of the headers. The headers can be quite long. They include information on how the message got here, when it was sent, who sent it, who it was sent to, and much more. We'll look at them in more detail on page 484.

The headers are separated from the message body by an empty line. The first part, which mutt displays in bold, is quoted text: by putting a > character before each line, the sender has signalized that the text was written by another person, often the person to whom it is addressed: this message is a reply, and the text is what he is replying to. Normally there is an attribution above the text, but it's missing in this example. We'll see attributions below in the section on replying.

If the message is longer than one screen, press SPACE to page down and - (hyphen) to page up. In general, a 25 line display is inadequate for reading mail. On an X display, choose as high a window as you can.